I have a new paper, with Kelsea Best and Bishawjit Mallick, in which we used pattern-oriented agent-based modeling to study environmentally-driven migration in rural Bangladesh and found that economic inequality in rural villages plays a crucial role.

Environmental stresses, such as floods, droughts, and severe storms, can play important roles in displacing populations and affecting both temporary and permanent migration away from people’s home communities. However, extensive research consistently finds that the connection between disasters or other environmental events and migration is not a simple matter of the event directly causing migration. Rather, environmental stress is best considered as one among many factors affecting population movements.

[T]hey did not react blindly to the furies of nature. What appears to be natural takes work: policies and legislation, chance and intention, technology and energy—not famine alone—combined to “push” migration across the Bay of Bengal. (Amrith 2013, 114)

Just as the environment is only one among many factors that drive migration, migration is also only one among many possible responses to environmental change. (Walsham 2010)

Additionally, for several years Bishawjit Mallick has been arguing that greater attention should be paid to environmental non-migration: active decisions not to migrate in the face of environmental stress.

To better understand the interactions between environmental and other forces in shaping people’s decisions whether to remain in their home communities or leave, we turned to pattern-oriented agent-based modeling. This method, which originated in ecological modeling, seeks to identify underlying mechanisms driving complex phenomena through a “multiscope” approach that identifies multiple qualitative patterns that a system exhibits at different scales, and evaluates models by their ability to simultaneously reproduce all the target patterns.

Identifying Patterns

The three of us have been studying migration in Bangladesh for a decade, including extensive collaborations with Amanda Carrico and Katharine Donato, who lead the ongoing Bangladesh Environment and Migraiton Survey. We have long been intrigued by unexpected patterns in environmentally-driven migration discovered by Clark Gray and Valerie Mueller, in which:

- Migration away from rural villages in Bangladesh are driven more by disasters that cause farmers to lose their crops than by disasters, such as floods, that affect other aspects of people’s lives and communities.

- When disasters cause crop losses that affect only a small fraction of a community, out-migration falls, compared to years when there is no disaster, but when the disaster affects the crops of more than about 20% of a community, out-migration rises.

- Households that are directly affected by a disaster are less likely to migrate away than households that are not directly affected.

Gray and Mueller’s findings are well-suited to study with pattern-oriented modeling, so we developed an agent-based model to investigate whether a simple economic model of a village could explain them.

Our model sought to reproduce the latter two patterns: (1) as a disaster affects more and more of a community, migration drops at first, and then rises when the scope of the disaster crosses a threshold, and (2) households that are directly affected by the disaster are less likely to migrate.

What We Did (Simple Overview)

We built our model on the hypothesis that households make decisions whether to send one or more members of their extended family to seek work outside the village, and do so based on whether they expect that they will see a net economic benefit from the remittances the migrant sends back, after paying for the cost of migration.

Our model simulates a village economy that provides both agricultural and non-agricultural opportunities for income. Households may have arable land on which they grow crops, and they may hire workers to help cultivate their fields and household members may seek income by working on others’ fields.

When a disaster causes crop losses, a household will no longer employ wage-laborers on its own fields, and members may seek to replace the lost income by working on others’ fields, and they may also seek non-farm employment.

We used empirical data from household surveys to assign values for most parameters that describe the village and the households, but we had to guess at two that were not addressed in surveys: the cost of migrating and seeking work elsewhere, and the expected value of remittances that migrants send back.

What We Found

After running the model tens of thousands of times, with many different combinations of estimates for the cost of migration, remittances from migrants, and the distribution of household land ownership, we found a surprising result:

As long as our model accurately represented the inequality of land-ownership within a village, it robustly reproduced the two target patterns from Gray and Mueller’s work. By “robustly”, we mean that model reproduced both patterns in the vast majority of simulation runs for 91% of the values we tested for the unknown parameters describing the expected cost and benefit of migration.

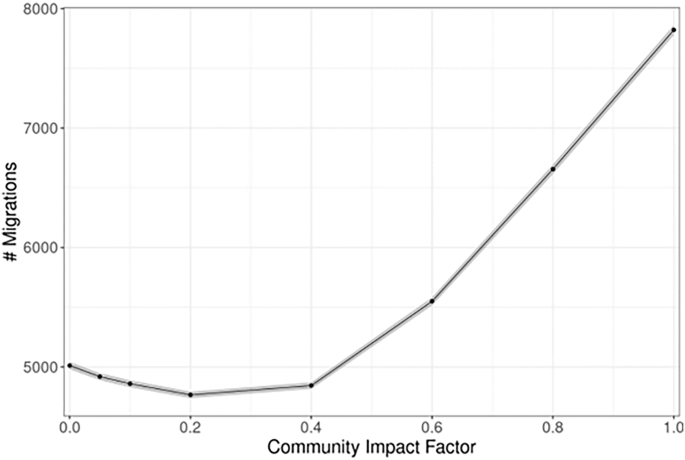

Figure 1: Variation of migration versus community impact factor

Variation in the number of migrations following a disaster, versus the fraction of the community affected (community impact-factor). The solid black line represents the mean from 13,7000 simulation runs, and the gray area represents the 95% confidence interval over those runs.

However, when we ran the model using distributions of land-ownership that did not represent what we knew from household surveys—especially distributions in which inequality in land-ownership was much less than the surveys revealed—the model performed poorly at reproducing the observed patterns.

Thus, we learned that a simple hypothesis that households make migration decisions based mostly upon the expected economic benefit is sufficient to explain observed patterns of migration, but only if the model gets the economic inequality correct.

This reveals that economic inequality within villages appears to be far more important than we expected at influencing decisions about migration after a disaster.

Details of Our Model

Our model determined employment using a continuous double-auction labor market that matches households seeking workers with workers seeking employment.

Each year, each household considers whether to send one or more members away to seek employment outside the village. They do this based on the opportunities available within the village, the cost of migration, and the expected benefit of migration in the form of remittances returned by the migrant.

Household size, wealth, income opportunities, and land-holdings were initialized from random distributions parameterized by empirical data collected by Carrico and Donato’s BEMS survey, which covered roughly 1,300 households in 10 communities. Two variables that were crucial for our model were not collected by the survey: the cost of migrating and the average remittance returned by migrants.

To address our uncertainty about these two variables, we ran the model 100 times for each of 150 random combinations of plausible cost and remittance. We used machine-learning methods to identify what combinations of parameters can reproduce both patterns at once.

Full details of the model, including a complete ODD specification, are available in the paper and its supplementary material, which are Open Accsess and freely available, and we have published the full model code on GitHub.